The "Blurred Lines" Between Originality and Art

Back in 2015, a Los Angeles federal jury found that Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams, the creative force behind the 2013 pop hit "Blurred Lines," had committed copyright infringement, using elements of the 1977 Marvin Gaye song "Got to Give It Up" in their composition, and without proper credit.

The "Blurred Lines" Copyright Ruling awarded Mr. Gaye's family approximately $7.3 million in profits from the song and related damages.

Ancient history, right?

Yes—and No, in that the case offers us a glimpse into how misconceptions about innovation can get in the way of how it really happens.

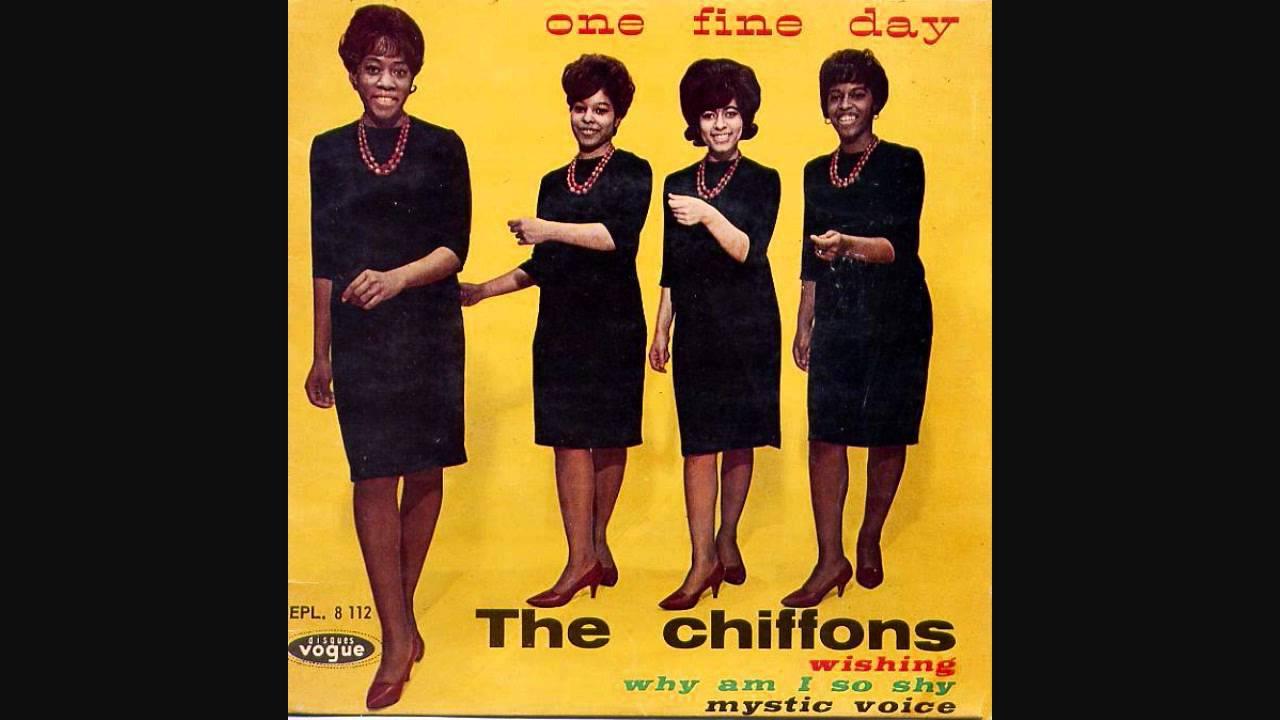

And this ruling was a repeat of a plagiarism suit in which former Beatle George Harrison faced charges that his 1970 hit song "My Sweet Lord" plagiarized the 1962's "He's So Fine" by the Chiffons.

Evidence showed the similarities between the songs, and the judge said it was "perfectly obvious—the two songs are virtually identical." The courts decided that roughly three-fourths of the money that Harrison made on his song and on its album were the direct result of similar notes used in the two songs.

Here is Harrison singing "My Sweet Lord"

and here are the Chiffons singing "He's So Fine."

The songs are certainly similar, and yet nobody would mistake one for the other.

This obsession with originality reminds me of the wonderful history of one of the most successful movies of all time, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

In 1978 George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and the screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan gathered in Hawaii for a "spitball session" to work through an idea for an adventure movie. A favorite Hollywood practice, spitball sessions involve a small group of creative types throwing around ideas around in hopes of sparking in each other yet more ideas that they each might never come up with on their own.

In 2013 New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe wrote "Spitballing Indy," informed by a transcript of the gathering on that Aloha state beach:

Lucas, Spielberg, and Kasdan come up with ideas for everything from the overarching plot to the characters to individual scenes. And they do so in the ways that we all tend to come up with new ideas: by bringing in bits and pieces from our past experiences. The origins of the hero, Indiana Jones, for example, draw directly from a mélange of previous heroes:

The hero, Lucas explains, is a globe-trotting archaeologist, "a bounty hunter of antiquities." He's a professor, a Ph.D.—"People call him doctor." But he's a little "rough and tumble." As the men hash out the Jones iconography, they refer, incessantly, to other films, invoking Eastwood, Bond, and Mifune. He will dress like Bogart in "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre," Lucas says: "the khaki pants—the leather jacket. That sort of felt hat." Oh, and also? "A bullwhip." He'll carry it "rolled up," Lucas continues. "Like a snake that's coiled up behind him."

StooTV has painstakingly pieced together a brilliant scene-by-scene anthology of the original B-movie inspirations that made the opening sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark: Raiders of the Lost Archives.

While almost every scene drew from previous movies, the result is widely considered the best opening sequence in film. Thus Lucas and Spielberg, themselves former film school students and lifelong movie buffs, entered the canon and are now feeding future auteurs. In an epic irony, the audio is not included, as youtube notes, because "This video previously contained a copyrighted audio track. Due to a claim by a copyright holder, the audio track has been muted."

The "Blurred Lines" ruling, like the Harrison/Chiffons ruling, establishes a strict notion of copyright violation which, if applied to the modern era, would rob of us of almost all major innovations. Edison's lightbulb came 40 years after the original incandescent bulbs were patented. Ford's Model-T came decades after the first commercial automobile. Apple's Macintosh computer built on Xerox's Alto, the iPod followed roughly a dozen MP3 players built for the PC platform, and the iPhone followed a trail blazed by the Blackberry and Treo. And Google's search engine also followed roughly a dozen other search engines.

So what is creativity?

To go way back, G.W. Bethune in 1837 defined creativity as the ability to "originat[e] new combinations of thought." In 1880 William James called it "the most unheard-of combinations of elements." Forty-two years later the sociologist William Fielding Ogburn defined it as a result of "combining existing and known elements of culture in order to form a new element."

Today, at the renowned international design and consulting firm IDEO, designers come up with creative solutions to new problems by tapping into their diverse experiences.

Their brainstorming sessions are identical to the Raiders spitball sessions. In pursuing innovation, teams look for new ideas in the combinations of things that have been done before, drawing on the long history of their own fields as well as the breadth of ideas in other fields.

Even the former Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant, not known as the most humble of celebrities, acknowledged:

"There's nothing that hasn't been done before. I seriously have stolen all of these moves from all these great players—I just try to do them proud, the guys who came before, because I learned so much from them. It's all in the name of the game. It's a lot bigger than me."

The difference between creativity and copying is how far afield you you look and how many different ideas you bring together. Who else has tried to solve this problem before? What did they do? What worked that we can build on? What can we add that was missing?

Creativity in perspective

If we insist on equating creativity with originality, we must ask two key questions:

First, how much does the value of any work of art—or anything, really—come from its inspirations, and how much comes from which inspirations are combined, in what particular ways, and to what audiences? Had George Harrison simply covered the Chiffons' teen love song and offered it to his audience in 1970, how well would it have sold?

Second, whenever we acknowledge the inspirations—the raw materials—of a successful innovation, we shouldn't stop there. We must ask, what inspired those inspirations? Who did the Chiffons borrow ideas from? What else did Harrison draw from?

I'll finish with this wonderful image of "the King of Boogie" John Lee Hooker and his diagram of the origins of blues music. It is too clever by half to point out when an artist copied from someone else and yet it is sublime humility when the artists themselves recognize in their work the threads that have run through everything that came before.